Home >> Art >> Painting >> History Four Treasures Masters Gallery Landscape Flowers Birds Famous Paintings

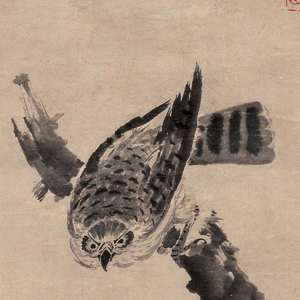

Over the course of Chinese painting, the three main subjects have been landscapes, birds-and-flowers, and figures. Flower painting, previously associated chiefly with Buddhist art, came into its own as a separate branch of painting in the Five Dynasties (907-960). Along with flowers came birds. At Chengdu in Sichuan, the master Huang Quan (黃筌, ca.903-965) developed the naturalistic style (xiesheng 寫生, “sketch life”, or lifelike painting) for painting birds. This technique was mainly adopted by professional or court painters, in contrast to the freehand style of “sketching ideas (xieyi, 寫意)”.

(Click on the thumbnails to view high resolution images.)

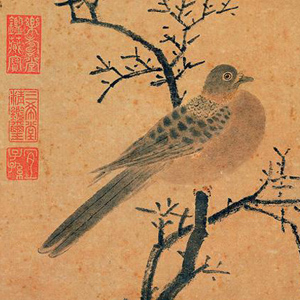

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the meticulous “sketch life” style was further developed by artists such as Cui Bai (崔白, ca.1044-1088). In addition, the northern Song emperors were enthusiastic patrons of the arts. The most renowned is Huizong, or Zhao Ji (趙佶, 1082-1135), perhaps the most knowledgeable of all Chinese emperors about the arts. Zhao Ji was himself an accomplished calligrapher (he developed a unique and extremely elegant style known as “slender gold”) and a painter chiefly of birds and flowers in the realistic tradition. While meticulous in detail, his works were subjective in mood, following poetic themes that were calligraphically inscribed on the painting. A fine example of the kind of painting attributed to him is the minutely observed and carefully painted Five-Colored Parakeet on Blossoming Apricot Tree (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). He demanded the same qualities in the work of his court painters and would add his cipher to pictures of which he approved. It is consequently very difficult to distinguish the work of the emperor from that of his favored court artists.

In the Yuan Dynasty, the restriction of the scholars' opportunities at court and the choice of many of them to withdraw into seclusion rather than serve the Mongols created a heightened sense of class identity and individual purpose, which in turn inspired their art. Qian Xuan (錢選, 1235-1305) was among the first to define this new direction. From Wuxing (吳興) in Zhejiang, he steadfastly declined an invitation to serve at court, as reflected in his painting style and themes. Before the Mongol conquest, however, Qian Xuan was a conservative painter, especially of realistic flowers and birds. Later he altered his style to incorporate the primitive qualities of ancient painting, favoring the Tang blue-and-green manner in his landscape painting, and stiff or peculiarly mannered renditions of vegetation and small animals.

On the other hand, the most distinguished of the scholar-painters was Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫, 1254–1322), a fellow townsman and younger follower of Qian Xuan who became a high official and president of the imperial Hanlin Academy in the Mongol court. In his official travels he collected paintings by Tang and Song masters that inspired him to revive and reinterpret the classical styles in his own fashion. Zhao Mengfu excelled in landscape painting (see his Autumn Colors), flower-and-bird painting, as well as calligraphy.

In the Ming Dynasty, court painters Bian Jingzhao (邊景昭, fl. early 15th century) and his follower Lü Ji (呂紀, 1477-?) carried forward the bird-and-flower painting tradition of Huang Quan, Cui Bai, and the Song emperor Huizong. Lü Ji's paintings display two distinct styles. Some of his works employ brilliant colors in a very meticulous rendition, while others are more fluid with light colors added to ink and wash, probably catering to the different tastes of the emperors he served.

Outside the court, the most outstanding Ming dynasty literati painter is Shen Zhou (沈周, 1427–1509). Shen Zhou was the pioneer of the Wu School of painting, in today’s Suzhou and Lake Tai region. He never became an official but instead devoted his life to painting and poetry. Shen Zhou commanded a wide range of styles and techniques, on which he impressed his warm and vigorous personality. He also became the first to establish among the literati painters a flower-and-bird painting tradition.

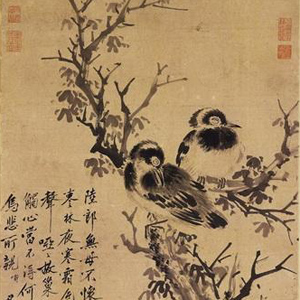

Shen Zhou’s works, executed in the “sketching ideas (xieyi 寫意)” style, were followed with greater technical versatility by Chen Chun (陳淳, 1483-1544) and Xu Wei (徐渭, 1521-1593) in the Ming and then by Shitao (石濤, 1642-1707) and Zhu Da (朱耷, 1626-1705) of the early Qing. Their work, in turn, served as the basis for the revival of flower-and-bird painting in the late 19th and the 20th century.

In Zhu Da’s paintings, usually in ink monochrome, such creatures as birds and fishes are given a curious, glowering, sometimes even perverse personality. He used an abbreviated, wet style that, while deceptively simple, captures the very essence of the flowers, plants, and creatures he portrays. Unlike most Chinese painters, he does not easily fit into any traditional category; in character and personality he was the complete eccentric and “individualist.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Shanghai, which had been forcibly opened to the West in 1842 and boasted a newly wealthy clientele, was the logical site for the first modern innovations in Chinese art. A Shanghai regional style had appeared by the 1850s, led by Ren Xiong (任熊, 1823-1857), his more popular follower Ren Yi (任頤, Ren Bonian 任伯年, 1840-1896), and Ren Yi's follower Wu Changshuo (吳昌碩, 1844-1927). The style drew its inspiration from a series of aforementioned Individualist artists of the Ming and Qing. It focused on birds and flowers and figural themes more than the old landscape tradition did, and it emphasized decorative qualities, exaggerated stylization, and satiric humor rather than refined brushwork and sober classicism. Under Wu Changshuo's influence, this style was passed on to Beijing in the early 20th century through the art of Chen Shizeng and Qi Baishi.

Chen Shizeng (陳師曾, 1876-1923) came from a family of prominent officials and scholars. In 1902 Chen went to Japan for further study. While focusing on natural history, he continued to practice traditional Chinese painting and to study Western art. He stayed in Japan until 1910 — one year before the Republic of China was established — at which time he returned to China, taught art, and became prominent in artistic circles. Although not strictly conservative — he approved of experimenting with innovative techniques and learning from Western art — Chen believed in the value of traditional Chinese painting. His flower paintings were influenced by Ming Dynasty painters Chen Chun (陈淳) and Xu Wei (徐渭), and his landscape style was drawn from Shen Zhou (沈周) and Shitao (石涛), among others. Chen Shizeng was deeply concerned with the fate of traditional Chinese art, and he worked closely with the Japanese art historian Omura Seigai to stem the tide of modernization that was threatening the classical tradition. Together they published The Study of Chinese Literati Painting (中國文人畫之研究) in 1922, which examined the history of Chinese scholar-painters who incorporated their knowledge of poetry and other arts into their painting.

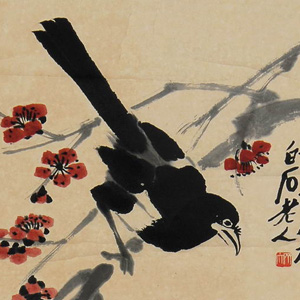

Qi Baishi (齊白石, 1864-1957) was another major artist in support of more traditional styles, who combined Shanghai style with an infusion of folk-derived vitality. Qi was of humble origins, and it was largely through his own efforts that he became adept at the arts of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal-carving. Some of Qi's major influences include the Ming Dynasty artist Xu Wei (徐渭) and the early Qing Dynasty painter Zhu Da (朱耷). In his forties, Qi Baishi began traveling and looking for more inspiration. He came upon the Shanghai School, which was very popular at the time, and met Wu Changshuo (吴昌硕) who then became another mentor to him and inspired a lot of his works. Another influence of Qi Baishi came about fifteen years later, as Qi became close to Chen Shizeng (陈师曾) after he settled down in Beijing. Qi Baishi theorized that “paintings must be something between likeness and unlikeness.” His prodigious output reflects a diversity of interests and experience, generally focusing on the smaller things of the world rather than the large landscape. Shrimp, fish, crabs, frogs, and peaches were his favorite subjects. Using heavy ink, bright colors, and vigorous strokes, he created works of a fresh and lively manner that expressed his love of nature and life.

On the other hand, the first Chinese artists to respond to international developments in modern art were those who had visited Japan, where the issues of modernization appeared earlier than they did in China. Among the first Chinese artists to bring back Japanese influence were Gao Jianfu (高劍父, 1879-1951), his brother Gao Qifeng (高奇峰, 1889-1933), and Chen Shuren (陳樹人, 1884-1948). Gao Jianfu studied art for four years in Japan, beginning in 1898; during a second trip there, he met Sun Yat-sen, and subsequently, in Guangzhou (Canton), he participated in the uprisings that paved the way for the fall of imperial rule and the establishment of a republic in 1911. Inspired by the “New Japanese Style,” the Gao brothers and Chen inaugurated a “New National Painting” movement, which in turn gave rise to a Cantonese, or Lingnan (“Range South”, 嶺南), regional style that incorporated Euro-Japanese characteristics. Although the new style did not produce satisfying or lasting solutions, it was a significant harbinger and continued to thrive in Hong Kong, practiced by such artists as Zhao Shao'ang (趙少昂, 1905-1998).

The first establishment of Western-style art instruction also dates from this period. A small art department was opened in Nanjing High Normal School in 1906, and the first art academy, later to become the Shanghai Art School, was founded in 1912, by the 16-year-old Liu Haisu (劉海粟, 1896-1994). Increasingly, by the mid-1920s, young Chinese artists were attracted not just to Japan but also to Paris and German art centers. A trio of these artists brought back some understanding of the essential contemporary European traditions and movements. Liu Haisu was first attracted to Impressionist art, while Lin Fengmian (林風眠, 1900-1991), who became director of the National Academy of Art in Hangzhou in 1928, was inspired by the experiments in color and pattern of Henri Matisse and the Fauves. Lin advocated a synthesis combining Western techniques and Chinese expressiveness and left a lasting mark on the modern Chinese use of the brush. Another major artist, Xu Beihong (徐悲鴻, 1895-1953), head of the National Central University's art department in Nanjing, eschewed European Modernist movements in favor of more conservative Parisian academic styles. He developed his facility in drawing and oils, later learning to imitate pencil and chalk with the Chinese brush. The monumental figure paintings he created would serve as a basis for Socialist Realist painters after the communist revolution of 1949.