We are inviting you to our NEW home COMuseum.com in 10 seconds!

Home >> Art >> Painting >> History Four Treasures Masters Gallery Landscape Flowers Birds Famous Paintings

Many critics consider landscape to be the highest form of Chinese painting. By the late Tang Dynasty (618-907), landscape painting had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. As the Tang Dynasty disintegrated, the concept of withdrawal into the natural world became a major thematic focus of poets and painters. Faced with the failure of the human order, learned men sought permanence within the natural world, retreating into the mountains to find a sanctuary from the chaos of dynastic collapse.

The time from the Five Dynasties period to the Northern Song period (907-1127) is known as the "Great age of Chinese landscape". In the north, artists such as Fan Kuan (範寬) and Guo Xi (郭熙) painted pictures of towering mountains, using strong black lines, ink wash, and sharp, dotted brushstrokes to suggest rough stone. In the south, Dong Yuan (董源) and Juran (巨然) painted the rolling hills and rivers of their native countryside in peaceful scenes done with softer, rubbed brushwork. These two kinds of scenes and techniques became the classical styles of Chinese landscape painting.

In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), landscapes of

more subtle expression appeared; immeasurable distances were conveyed

through the use of blurred outlines, mountain contours disappearing

into the mist, and impressionistic treatment of natural phenomena.

Emphasis was placed on the spiritual qualities of the painting and on

the ability of the artist to reveal the inner harmony of man and

nature, as perceived according to Taoist and Buddhist concepts.

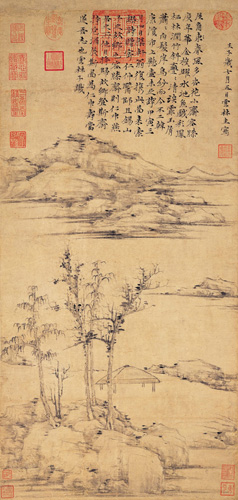

Under the Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), when many educated Chinese were barred from government service, the model of the Song literati retreat evolved into a full-blown alternative culture as this disenfranchised elite transformed their estates into sites for literary gatherings and other cultural pursuits. These gatherings were frequently commemorated in paintings that, rather than presenting a realistic depiction of an actual place, conveyed the shared cultural ideals of a reclusive world through a symbolic shorthand in which a villa might be represented by a humble thatched hut. Because a man's studio or garden could be viewed as an extension of himself, paintings of such places often served to express the values of their owner. Painting was no longer about the description of the visible world; it became a means of conveying the inner landscape of the artist's heart and mind. The most famous painters of this period include Zhao Mengfu (趙孟頫), and the Four Masters of the Yuan, namely Huang Gongwang (黃公望), Wang Meng (王蒙), Ni Zan (倪瓚), and Wu Zhen (吳鎮).

Famous Paintings:

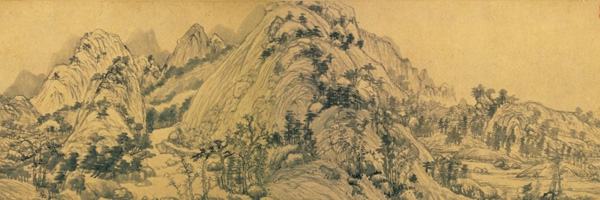

During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), when native Chinese rule was restored, court artists produced conservative images that revived the Song metaphor for the state as a well-ordered imperial garden, while literati painters pursued self-expressive goals through the stylistic language of Yuan scholar-artists. Shen Zhou (沈周), the patriarch of the Wu school of painting centered in the cosmopolitan city of Suzhou, and his preeminent follower Wen Zhengming (文徵明) exemplified Ming literati ideals. Both men chose to reside at home rather than follow official careers, devoting themselves to self-cultivation through a lifetime spent reinterpreting the styles of Yuan scholar-painters.

Famous Painting: Lofty Mount Lu by Shen Zhou

Morally charged images of reclusion remained a potent political symbol during the early years of the Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), a period in which many Ming loyalists lived in self-enforced retirement. Often lacking access to important collections of old masters, loyalist artists drew inspiration from the natural beauty of the local scenery.

Images of nature have remained a potent source of inspiration for artists down to the present day. While the Chinese landscape has been transformed by millennia of human occupation, Chinese artistic expression has also been deeply imprinted with images of the natural world. Viewing Chinese landscape paintings, it is clear that Chinese depictions of nature are seldom mere representations of the external world. Rather, they are expressions of the mind and heart of the individual artists—cultivated landscapes that embody the culture and cultivation of their masters.